Automating bug bounties

I have bad news…. I first noticed this one day like any other, and once I noticed it, I couldn’t escape the reality. Hacking is boring. This may seem counter-intuitive at first. If you looked at your average hacker, they wouldn’t look bored. More like a mixture of stressed and angry/depressed, probably.

But spend a day in their shoes and you’ll come to the same conclusion. Every attempt at hacking is basically a series of steps, tediously, methodically followed.

Let me paint you a picture. You’ve been told by your boss that you need to hack this web application. You don’t want to; you just came back from your holidays and it’s too hot in the office. It looks pretty old and, for the sake of making it more interesting, it seems that it is running PHP. After poking at it for approximately 10 seconds, you’d have a nice idea of what is going on, but you need to perform endpoint discovery.

Endpoint discovery is performed through various dull means, such as crawling, manually navigating, brute-forcing folders, and looking at source code. None of these things will strike you as being particularly fun. But if you are serious about your job you will do these things and perform them to an “acceptable standard”.

What an “acceptable standard” is has not been clearly defined, so unfortunately each pentester will have their own approach: some will be extremely thorough (to the point they’ll lose their minds), while others will have a look-see and hope they find enough bugs to say they’ve done their job, despite missing like 30% of the application.

This application has acquired a lot of cruft over the years, and let’s say it has 500 endpoints.

Let’s assume for each of the 500 endpoints, if they have an average of 5 parameters in each, you now have 2500 insertion points to duly check. You COULD in theory filter those out and not test them all. For example, you could not test the User-Agent header in all 500 endpoints; and to be fair, most people don’t. But everybody knows that bugs are lurking everywhere, and there’s no compelling logical reason to not test all parameters for every vulnerability type. One of those 500 endpoints could have SQL injection in the User-Agent header; and if you don’t test it, you won’t find it.

Going back to those 2500 insertion points: realistically, it’s not feasible to test for every vulnerability type, so you will do your best to test to an “acceptable standard”. An exhaustive test of an application would involve at least a majority of these parameters:

- A manual review. Like, put quotes and see if it breaks in a big way. Is the input reflected in the response? If so: is it escaped? If not: would the Content-Type header allow for reflected XSS attacks? Is it an identifier? Can you replace that identifier with another user’s identifier? Etcetera.

- Manual fuzzing. Send a list of known payloads using a tool like intruder. Because each parameter may need specific encoding, make sure you configured that correctly. For each parameter, inspect the results. Did your authentication expire while you were fuzzing? Redo it. CSRF tokens? You need to account for those.

- Automated fuzzing. Run that through burp’s automated scanner and backslash-powered scanner, and see if it finds a bug. Is the scanner scanning the logout page and expiring your session? Redo the whole scan. Is it dealing with CSRF tokens? No? You need to deal with that.

This is mind-numbingly boring and extremely error-prone. Initially, I was attracted to the challenge of finding bugs in itself; but once you’ve found hundreds, or maybe thousands of bugs, the thrill of finding them is rather short-lived and provides a poor motivator. Additionally, finding an RCE loses its luster if what you’re hacking is the technological equivalent of Swiss cheese.

Moving forward from this

All of this is extremely tedious. This results in hackers creating automated tools in order to automate these tasks, but the problem space is very large, and no tool can effectively do this in all cases, so you will definitely still have to do a big, boring, portion of the tasks manually.

In the case of pentesters this is definitely true. You are paid to test to an “acceptable standard” and no automated tool could ever be considered to meet that. In my case however, because I do bug bounties, the bugs I miss are irrelevant, and nobody realistically expects every bug bounty hunter to find every bug. There is even a debate about the effectiveness of bug bounties at all, mind you.

But to the point, the bugs I miss don’t matter, only the ones I find and report.

Another issue which is relevant to bug bounty hunters and not pentesters is time to find and time to report. When I find a bug and somebody else found it first, I get $0 and they get $200. If I find it first the situation is reversed, so there is a big incentive to push hard and fast to be the early bird. Due to personal reasons, I am frequently unable to spend a lot of time hacking so it happens a lot that in events and things like that younger hackers with more free time tend to find and report the bugs first.

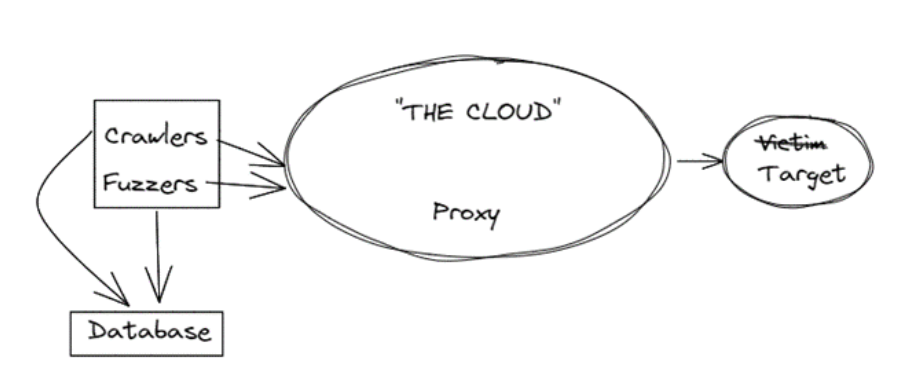

Due to these reasons and many others, I found myself automating more and more of my workflow. I have gone through several iterations and eventually found an architecture that I personally quite like, which I wanted to share with others because I think from a software development perspective it is quite interesting, and I think more collaboration in this space will result in a better outcome for everybody.

Generally in the bug bounty community there’s a certain secrecy. It is not entirely irrational because for every bit of information you give away there is a possibility it will be used to snatch a bug from you. Personally I think that attitude, while functional at some level, leads to very poor outcomes for the industry as a whole and we should all be negotiating collectively for better outcomes for all bug bounty hunters as a whole.

A bit of background information

Some constraints and characteristics underline your thinking whenever you write software to identify or automatically exploit software vulnerabilities. To make a long story short, people don’t like it when you hack them, and people don’t want to be complicit in hacking other people.

In particular, ISPs don’t like it when you use their servers to hack other people’s servers, and they may ban your account in relation to this, even if you have permission from any target. If you have a database of findings, and an ISP bans your account for breaching their terms of service they may or may not return a copy of your data. This could be a bummer if you have a bunch of bugs in there, and it means you need to bring your infrastructure back up. If your infrastructure was held together by a couple of wires and duct tape, you need to do that again. Reproducible infrastructure is so important in this case for this reason.

Another aspect is that bug bounty programs don’t like it when people run automated tasks against them and may rate-limit your connections or outright ban your IP. This is good, because it means that if you make a mistake, they’ll ban your IP instead of you knocking their site offline, but it means you get false negatives.

Another thing to consider is that hosting is very expensive, and hacking can be very computationally expensive. In particular, if you are hacking a lot of things at the same time you need a lot of CPU, a lot of RAM and a lot of bandwidth. If you are considering storing requests and responses for later analysis you need lots of hard disk space.

A major pain point for me is that most of the time all that hardware is sitting idle. Sure, you may hack for three hours a day during the week and you need results as fast as possible then, but the rest of the time all that sweet computing power is wasted and your VPS is profiting off of your inactivity. So I wanted to create an architecture that takes that into account.

Automating the boredom away

When I decided to automate my bug bounty process, I had the following principles in mind:

- High quality bugs only: I’m only interested in bugs which have a high impact. RCE, SQLi, SSRF, XSS, content injection. No “missing header,” outdated JS library type things.

- Fully automated: should require minimal input from me. I don’t want to be hacking a website ever again. Everything that can be automated should be automated. Things that can’t be automated shouldn’t be automated obviously, like logging in to websites and the like.

- Authenticated scanning only. There are enough people trying to perform unauthenticated scans already.

- Reproducible infrastructure. As mentioned before, we want to be able to seamlessly bring up and down servers using Saltstack.

- Not particularly sophisticated: It should employ simple techniques proven to find lots of bugs across a large number of websites in a repeatable manner. Think like backslash powered scanner and shelling combined into one, minus burp.

- Distributed: workloads should be distributable across multiple worker processes that can be spun up and shut down.

Because hardware is expensive, I want to be able to make use of the hardware I have in my home which are several gaming PCs and a couple of gaming laptops. If I make bank, I want to migrate the thing to the cloud entirely.

I identified the need for the following software components:

- A http proxy server that distributes requests across a number of worker processes. This allows my fuzzer and crawler components to be able to send request to a standard http proxy.

- Workers. These are in charge of sending requests to their final destination and returning any response data. The worker processes could be run on several hosts and source IP addresses.

- Crawlers. These are in charge of authenticating against the target websites and performing crawls. We’ve moved on from web 1.0 so these need to be browser-based, using playwright.

- Fuzzers. These authenticate requests and perform injection-based attacks as well as pingback-based attacks similar to collaborator.

- Database. Store credentials, bugs, scope and request/response data in a database.

- A login manager. We need to reliably authenticate to the target systems for crawling and fuzzing.

- Pingback DNS listener. A utility that listens for DNS pingbacks, correlates them to a specific request, parameter and vulnerability type and stores it in the database.

Status of the project

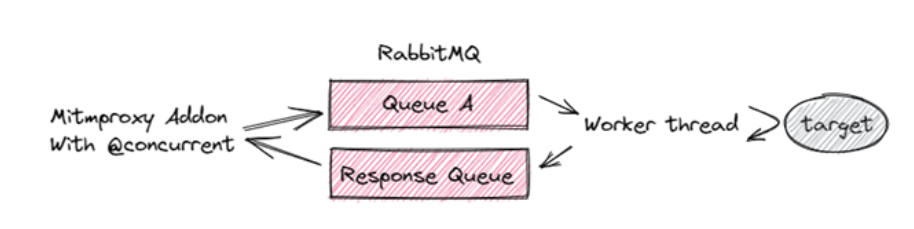

I have been working on this for a couple of months, maybe half a year part-time. It’s been really challenging in several aspects, mainly in its scope. Each of these components has lead me to learn new technologies and interfacing with technologies that I already knew in different ways. For example, creating the proxy led me to learn RabbitMQ for distributed workload management. Additionally, I created a mitmproxy plugin, which I had done before, but this plugin interfaced with that software project in a way that I hadn’t personally done, and probably nobody in their sound mind should as it is pretty far out.

I have currently fully functional versions of the proxy server and worker in Python, the web crawler interfacing with Playwright in Typescript. The fuzzer and pingback DNS listener are also implemented in Python, and the database is maintained using SQLAlchemy and PostgreSQL. I am about to start working on the orchestration which is in charge of feeding RabbitMQ the appropriate load for the available hardware, and looking to distribute the Crawlers so that I can fully make use of the hardware I have at my disposal. I also need to crawl bug bounty sites through their API.

Distributed HTTP proxy

I mentioned before several requirements that our solution should meet. In particular, we need to be able to rotate IPs and change hosts rapidly in the event of a ban. I decided to expose this functionality through a HTTP proxy, implemented in the form of a mitmproxy addon. Because most security tools are exposed through HTTP proxies, this provides interoperability with other tools such as Burp if needed.

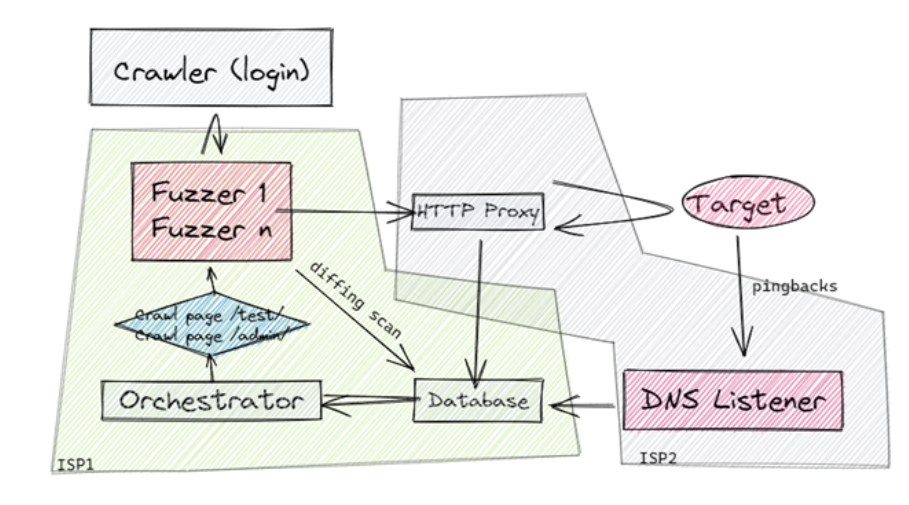

Here is a diagram for what I already have in place, which works OK.

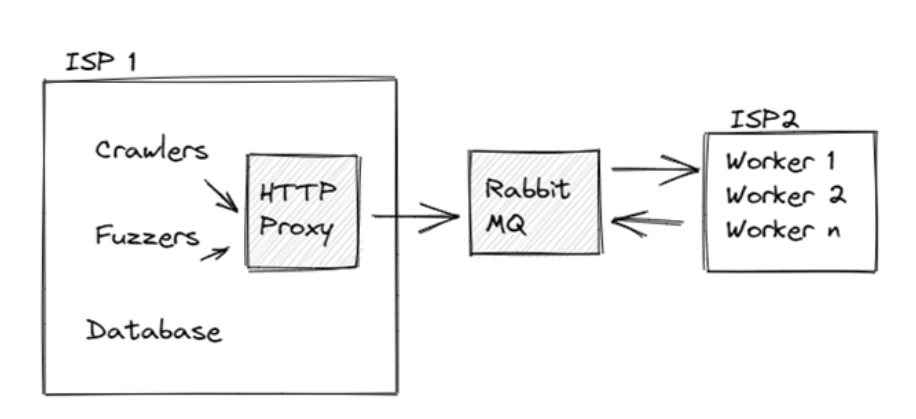

My plan involves two ISPs, and looks as follows:

For now, ISP 1 is my home’s ISP, but I could change that if needed. This is useful because any “malicious” traffic originates from ISP2 so if I get banned only my worker threads will be banned and no data will be lost.

I was originally concerned about any potential delays this could cause in terms of message throughput and such. I discovered that RabbitMQ is truly very fast and that mitmproxy does not introduce any significant delays either. From my analysis, approximately 99% of delays seem to come from my very slow, non-optimized python code. Here’s what I implemented. This follows the RabbitMQ RPC pattern:

The proxy is also in charge of writing data to the database. I implemented this using Python’s synchronized queue class to prevent the threads in charge of responding to users from slowing down through the integration with the database, as well as database write batching. I published the source code for this component here.

Crawler

When I started working on this project, one of the biggest concerns I had was the proliferation of JavaScript single-page applications. These cannot be crawled with regular crawlers such as Scrapy, and are generally a pain. Burp for example has functionality to crawl these in theory but I have personally found that it is a little bit fickle and painfully slow.

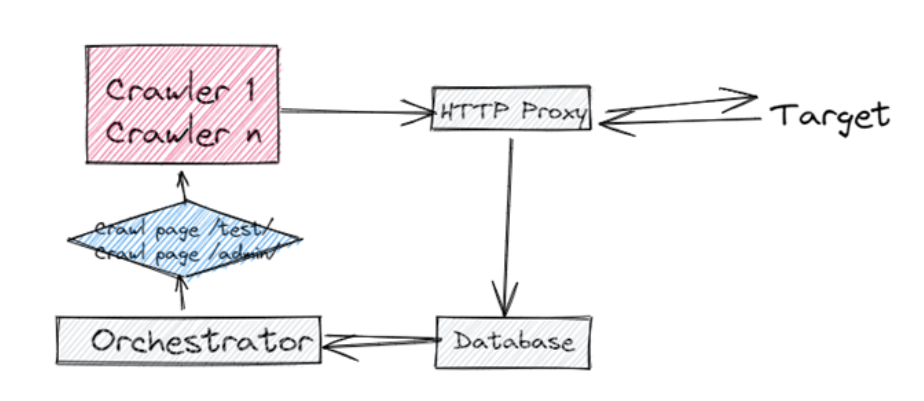

I looked into various options, such as puppeteer, some paid crawlers and similar. In the end I decided to implement this functionality using Playwright, a modern testing library very similar to Selenium in ye olde times. It is actually remarkably simple to configure, and my crawling strategy is very simple for now. In each page:

- Login and,

- Middle click all links.

- Click all links while blocking navigation.

- Fill and submit all forms present on the page.

- Close the browser.

This results in whatever is opened to be stored in the database through the proxy. On our next iteration these newly discovered pages will be crawled, and newly discovered pages will be stored in the database. The main advantage of this approach is that it is stateless. Each crawler process deals with a single page and then stores the results in the database, and this allows me to scale this to the amount of hardware I have.

I considered other approaches highlighted in various whitepapers I didn’t read but decided against them in principle because they need to keep a complete state of the navigation, for example, or had other disadvantages presumably. Obviously, all components in this solution can be updated and changed in the future. The good thing about my stateless approach is that if I implement a new change, then I can simply re-run the crawler with the new functionality on all URLs stored in the database.

Authentication is performed using Playwrights “code generator” that creates a login script that stores the state in a playwright state file.

Fuzzer

Creating a fuzzer is quite challenging. Web application vulnerabilities are quite diverse in how you can detect them, and every payload you add is going to be useless most of the time because most inputs are not vulnerable. In my experience, traditional vulnerability scanners like Burp’s active scan are relatively good at finding bugs, but the amount of traffic they generate mean that you cannot feasibly scan all endpoints.

Recently in the last few years PortSwigger has come up with a new technique in a Burp addon named Backslash Powered Scanner (BPS.) BPS has the capability of detecting a wide range of bugs while sending far less requests through two techniques: diffing scan and transformation scan. I currently implemented the diffing scan albeit with my special touch. Transformation scans are very powerful, and I certainly would look at implementing them in the future.

Another addon which I favour for bug bounty is SHELLING. The author of shelling created a series of very good, realistic test cases for remote code execution that could potentially be missed by traditional active scanning due to character blacklisting or whitelisting. I think this approach is obviously very valuable and thorough but the number of payloads it generates is very large. I made use of the test cases stored within that library and implemented my own detection via a DNS pingback. Since I already had a DNS pingback detection, I added a SSRF detector, as well as a XSS detector which could be triggered by the crawler in the case of stored XSS and picked up by XSS hunter.

The pingback detection takes the form of a DNS listener which parses the domains passed. An example pingback may look like follows:

xx<PROJECT_ID>.<REQ_ID>.<PARAM_NAME>.<BUG_TYPE>.mydomain.com

Based on this information we can store the pingback as a finding in the database. The architecture for the fuzzer is also stateless and makes use of the crawler for logging in to the website and fetching login cookies. Integrating the login process to each fuzz request allows us to ensure that we are fuzzing a logged in page, and not a session expired page. This is a big problem in burp where most of your requests will be logged out by the time active scanner reaches them. You can work around this in burp of course with the cookie jar and macros etc.

In conclusion

As well as completely shatter the impression that hackers have a meaningful and fulfilling life, in this blog post I have shown at high level an overview of this cool project I’m working on. It’s still early days for the project so there’s a lot to flesh out and lots of decisions to make, but I’m hoping that people find it interesting and am keen to hear if people have any ideas regarding automated hacking architecture and design.

Additionally, because of the stateless nature of the scanning I can in the future perform improved crawling or fuzzing using new techniques as they pop up. We’ll see.

I’ve also glossed over certain aspects of the design, such as the interaction between the ISPs or the database design. These are interesting details that I also put a lot of care into. Another aspect of the project that I’m interested in sharing is unit testing and integration testing which I am a big fan of.